Click here if you are looking for a certified online tutor or home tutor The word cell refers to several types of organisms. Cells such as paramecia, dinoflagellates, diatoms, and spirochetes are self-maintaining organisms; cells such as lymphocytes, erythrocytes, muscle cells, nerve cells, cardiac muscle, and chloroplasts are more specialized cells that are a part of higher multicellular organisms. Regardless of size or whether the cell is a complete organism or just part of an organism, all cells have certain structural components in common. All cells have some type of outer cell boundary that permits some materials to leave and enter the cell and a cell interior composed of a water-rich, fluid material called cytoplasm that contains hereditary material in the form of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). |

Chloroplasts

An examination of leaves, stems, and other types of plant tissue

reveals the presence of tiny green, spherical structures called chloroplasts,

visible here in the cells of an onion. Chloroplasts are essential to the

process of photosynthesis, in which captured sunlight is combined with water

and carbon dioxide in the presence of the chlorophyll molecule to produce

oxygen and sugars that can be used by animals. Without the process of

photosynthesis, the atmosphere would not contain enough oxygen to support

animal life.

|

| Cell , basic unit of life. Cells are the smallest structures capable of basic life processes, such as taking in nutrients, expelling waste, and reproducing. All living things are composed of cells. Some microscopic organisms, such as bacteria and protozoa, are unicellular, meaning they consist of a single cell. Plants, animals, and fungi are multi-cellular; that is, they are composed of a great many cells working in concert. But whether it makes up an entire bacterium or is just one of trillions in a human being, the cell is a marvel of design and efficiency. Cells carry out thousands of biochemical reactions each minute and reproduce new cells that perpetuate life. |

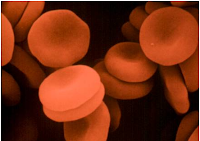

Cells vary considerably in size. The smallest

cell, a type of bacterium known as a mycoplasma, measures 0.0001 mm (0.000004

in) in diameter; 10,000 mycoplasmas in a row are only as wide as the diameter of

a human hair. Among the largest cells are the nerve cells that run down a

giraffe’s neck; these cells can exceed 3 m (9.7 ft) in length. Human cells also

display a variety of sizes, from small red blood cells that measure 0.00076 mm

(0.00003 in) to liver cells that may be ten times larger. About 10,000

average-sized human cells can fit on the head of a pin.

Along with their differences in size, cells

present an array of shapes. Some, such as the bacterium Escherichia coli,

resemble rods. The paramecium, a type of protozoan, is slipper shaped; and the

amoeba, another protozoan, has an irregular form that changes shape as it moves

around. Plant cells typically resemble boxes or cubes. In humans, the outermost

layers of skin cells are flat, while muscle cells are long and thin. Some nerve

cells, with their elongated, tentacle-like extensions, suggest an octopus.

In multicellular organisms, shape is typically

tailored to the cell’s job. For example, flat skin cells pack tightly into a

layer that protects the underlying tissues from invasion by bacteria. Long, thin

muscle cells contract readily to move bones. The numerous extensions from a

nerve cell enable it to connect to several other nerve cells in order to send

and receive messages rapidly and efficiently.

By itself, each cell is a model of

independence and self-containment. Like some miniature, walled city in perpetual

rush hour, the cell constantly bustles with traffic, shuttling essential

molecules from place to place to carry out the business of living. Despite their

individuality, however, cells also display a remarkable ability to join,

communicate, and coordinate with other cells. The human body, for example,

consists of an estimated 20 to 30 trillion cells. Dozens of different

kinds of cells are organized into specialized groups called tissues. Tendons and

bones, for example, are composed of connective tissue, whereas skin and mucous

membranes are built from epithelial tissue. Different tissue types are assembled

into organs, which are structures specialized to perform particular functions.

Examples of organs include the heart, stomach, and brain. Organs, in turn, are

organized into systems such as the circulatory, digestive, or nervous systems.

All together, these assembled organ systems form the human body.

The components of cells are molecules,

nonliving structures formed by the union of atoms. Small molecules serve as

building blocks for larger molecules. Proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates,

and lipids, which include fats and oils, are the four major molecules that

underlie cell structure and also participate in cell functions. For example, a

tightly organized arrangement of lipids, proteins, and protein-sugar compounds

forms the plasma membrane, or outer boundary, of certain cells. The organelles,

membrane-bound compartments in cells, are built largely from proteins.

Biochemical reactions in cells are guided by enzymes, specialized proteins that

speed up chemical reactions. The nucleic acid deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)

contains the hereditary information for cells, and another nucleic acid,

ribonucleic acid(RNA), works with DNA to build the thousands of proteins the

cell needs.

| II | CELL STRUCTURE |

Cells fall into one of two categories:

prokaryotic or eukaryotic (see Prokaryote). In a prokaryotic cell, found

only in bacteria and archaebacteria, all the components, including the DNA,

mingle freely in the cell’s interior, a single compartment. Eukaryotic cells,

which make up plants, animals, fungi, and all other life forms, contain numerous

compartments, or organelles, within each cell. The DNA in eukaryotic cells is

enclosed in a special organelle called the nucleus, which serves as the cell’s

command center and information library. The term prokaryote comes from

Greek words that mean “before nucleus” or “prenucleus,” while eukaryote

means “true nucleus.”

| A | Prokaryotic Cells |

Prokaryotic cells are among the tiniest of

all cells, ranging in size from 0.0001 to 0.003 mm (0.000004 to 0.0001 in) in

diameter. About a hundred typical prokaryotic cells lined up in a row would

match the thickness of a book page. These cells, which can be rodlike,

spherical, or spiral in shape, are surrounded by a protective cell wall. Like

most cells, prokaryotic cells live in a watery environment, whether it is soil

moisture, a pond, or the fluid surrounding cells in the human body. Tiny pores

in the cell wall enable water and the substances dissolved in it, such as

oxygen, to flow into the cell; these pores also allow wastes to flow out.

Pushed up against the inner surface of the

prokaryotic cell wall is a thin membrane called the plasma membrane. The plasma

membrane, composed of two layers of flexible lipid molecules and interspersed

with durable proteins, is both supple and strong. Unlike the cell wall, whose

open pores allow the unregulated traffic of materials in and out of the cell,

the plasma membrane is selectively permeable, meaning it allows only certain

substances to pass through. Thus, the plasma membrane actively separates the

cell’s contents from its surrounding fluids.

While small molecules such as water,

oxygen, and carbon dioxide diffuse freely across the plasma membrane, the

passage of many larger molecules, including amino acids (the building blocks of

proteins) and sugars, is carefully regulated. Specialized transport proteins

accomplish this task. The transport proteins span the plasma membrane, forming

an intricate system of pumps and channels through which traffic is conducted.

Some substances swirling in the fluid around the cell can enter it only if they

bind to and are escorted in by specific transport proteins. In this way, the

cell fine-tunes its internal environment.

The plasma membrane encloses the

cytoplasm, the semifluid that fills the cell. Composed of about 65 percent

water, the cytoplasm is packed with up to a billion molecules per cell, a rich

storehouse that includes enzymes and dissolved nutrients, such as sugars and

amino acids. The water provides a favorable environment for the thousands of

biochemical reactions that take place in the cell.

Within the cytoplasm of all prokaryotes is

deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), a complex molecule in the form of a double helix, a

shape similar to a spiral staircase. The DNA is about 1,000 times the length of

the cell, and to fit inside, it repeatedly twists and folds to form a compact

structure called a chromosome. The chromosome in prokaryotes is circular, and is

located in a region of the cell called the nucleoid. Often, smaller chromosomes

called plasmids are located in the cytoplasm. The DNA is divided into units

called genes, just like a long train is divided into separate cars. Depending on

the species, the DNA contains several hundred or even thousands of genes.

Typically, one gene contains coded instructions for building all or part of a

single protein. Enzymes, which are specialized proteins, determine virtually all

the biochemical reactions that support and sustain the cell.

Also immersed in the cytoplasm are the

only organelles in prokaryotic cells—tiny bead-like structures called ribosomes.

These are the cell’s protein factories. Following the instructions encoded in

the DNA, ribosomes churn out proteins by the hundreds every minute, providing

needed enzymes, the replacements for worn-out transport proteins, or other

proteins required by the cell.

While relatively simple in construction,

prokaryotic cells display extremely complex activity. They have a greater range

of biochemical reactions than those found in their larger relatives, the

eukaryotic cells. The extraordinary biochemical diversity of prokaryotic cells

is manifested in the wide-ranging lifestyles of the archaebacteria and the

bacteria, whose habitats include polar ice, deserts, and hydrothermal vents—deep

regions of the ocean under great pressure where hot water geysers erupt from

cracks in the ocean floor.

| B | Eukaryotic Animal Cells |

The eukaryotic cell cytoplasm is similar

to that of the prokaryote cell except for one major difference: Eukaryotic cells

house a nucleus and numerous other membrane-enclosed organelles. Like separate

rooms of a house, these organelles enable specialized functions to be carried

out efficiently. The building of proteins and lipids, for example, takes place

in separate organelles where specialized enzymes geared for each job are

located.

The nucleus is the largest organelle in an

animal cell. It contains numerous strands of DNA, the length of each strand

being many times the diameter of the cell. Unlike the circular prokaryotic DNA,

long sections of eukaryotic DNA pack into the nucleus by wrapping around

proteins. As a cell begins to divide, each DNA strand folds over onto itself

several times, forming a rod-shaped chromosome.

The nucleus is surrounded by a

double-layered membrane that protects the DNA from potentially damaging chemical

reactions that occur in the cytoplasm. Messages pass between the cytoplasm and

the nucleus through nuclear pores, which are holes in the membrane of the

nucleus. In each nuclear pore, molecular signals flash back and forth as often

as ten times per second. For example, a signal to activate a specific gene comes

in to the nucleus and instructions for production of the necessary protein go

out to the cytoplasm.

Attached to the nuclear membrane is an

elongated membranous sac called the endoplasmic reticulum. This organelle

tunnels through the cytoplasm, folding back and forth on itself to form a series

of membranous stacks. Endoplasmic reticulum takes two forms: rough and smooth.

Rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) is so called because it appears bumpy under a

microscope. The bumps are actually thousands of ribosomes attached to the

membrane’s surface. The ribosomes in eukaryotic cells have the same function as

those in prokaryotic cells—protein synthesis—but they differ slightly in

structure. Eukaryote ribosomes bound to the endoplasmic reticulum help assemble

proteins that typically are exported from the cell. The ribosomes work with

other molecules to link amino acids to partially completed proteins. These

incomplete proteins then travel to the inner chamber of the endoplasmic

reticulum, where chemical modifications, such as the addition of a sugar, are

carried out. Chemical modifications of lipids are also carried out in the

endoplasmic reticulum.

The endoplasmic reticulum and its bound

ribosomes are particularly dense in cells that produce many proteins for export,

such as the white blood cells of the immune system, which produce and secrete

antibodies. Some ribosomes that manufacture proteins are not attached to the

endoplasmic reticulum. These so-called free ribosomes are dispersed in the

cytoplasm and typically make proteins—many of them enzymes—that remain in the

cell.

The second form of endoplasmic reticulum, the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER), lacks ribosomes and has an even surface. Within the winding channels of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum are the enzymes needed for the construction of molecules such as carbohydrates and lipids. The smooth endoplasmic reticulum is prominent in liver cells, where it also serves to detoxify substances such as alcohol, drugs, and other poisons.

Proteins are transported from free and

bound ribosomes to the Golgi apparatus, an organelle that resembles a stack of

deflated balloons. It is packed with enzymes that complete the processing of

proteins. These enzymes add sulfur or phosphorus atoms to certain regions of the

protein, for example, or chop off tiny pieces from the ends of the proteins. The

completed protein then leaves the Golgi apparatus for its final destination

inside or outside the cell. During its assembly on the ribosome, each protein

has acquired a group of from 4 to 100 amino acids called a signal. The signal

works as a molecular shipping label to direct the protein to its proper

location.

Lysosomes are small, often spherical

organelles that function as the cell’s recycling center and garbage disposal.

Powerful digestive enzymes concentrated in the lysosome break down worn-out

organelles and ship their building blocks to the cytoplasm where they are used

to construct new organelles. Lysosomes also dismantle and recycle proteins,

lipids, and other molecules.

The mitochondria are the powerhouses of

the cell. Within these long, slender organelles, which can appear oval or bean

shaped under the electron microscope, enzymes convert the sugar glucose and

other nutrients into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). This molecule, in turn,

serves as an energy battery for countless cellular processes, including the

shuttling of substances across the plasma membrane, the building and transport

of proteins and lipids, the recycling of molecules and organelles, and the

dividing of cells. Muscle and liver cells are particularly active and require

dozens and sometimes up to a hundred mitochondria per cell to meet their energy

needs. Mitochondria are unusual in that they contain their own DNA in the form

of a prokaryote-like circular chromosome; have their own ribosomes, which

resemble prokaryotic ribosomes; and divide independently of the cell.

Unlike the tiny prokaryotic cell, the

relatively large eukaryotic cell requires structural support. The cytoskeleton,

a dynamic network of protein tubes, filaments, and fibers, crisscrosses the

cytoplasm, anchoring the organelles in place and providing shape and structure

to the cell. Many components of the cytoskeleton are assembled and disassembled

by the cell as needed. During cell division, for example, a special structure

called a spindle is built to move chromosomes around. After cell division, the

spindle, no longer needed, is dismantled. Some components of the cytoskeleton

serve as microscopic tracks along which proteins and other molecules travel like

miniature trains. Recent research suggests that the cytoskeleton also may be a

mechanical communication structure that converses with the nucleus to help

organize events in the cell.

| C | Eukaryotic Plant Cells |

Plant cells have all the components of

animal cells and boast several added features, including chloroplasts, a central

vacuole, and a cell wall. Chloroplasts convert light energy—typically from the

Sun—into the sugar glucose, a form of chemical energy, in a process known as

photosynthesis. Chloroplasts, like mitochondria, possess a circular chromosome

and prokaryote-like ribosomes, which manufacture the proteins that the

chloroplasts typically need.

In plant cells, a sturdy cell wall

surrounds and protects the plasma membrane. Its pores enable materials to pass

freely into and out of the cell. The strength of the wall also enables a cell to

absorb water into the central vacuole and swell without bursting. The resulting

pressure in the cells provides plants with rigidity and support for stems,

leaves, and flowers. Without sufficient water pressure, the cells collapse and

the plant wilts.

| III | CELL FUNCTIONS |

To stay alive, cells must be able to carry out a variety of functions. Some cells must be able to move, and most cells must be able to divide. All cells must maintain the right concentration of chemicals in their cytoplasm, ingest food and use it for energy, recycle molecules, expel wastes, and construct proteins. Cells must also be able to respond to changes in their environment.

| A | Movement |

Many unicellular organisms swim, glide, thrash, or crawl to search for food and escape enemies. Swimming organisms often move by means of a flagellum, a long tail-like structure made of protein. Many bacteria, for example, have one, two, or many flagella that rotate like propellers to drive the organism along. Some single-celled eukaryotic organisms, such as euglena, also have a flagellum, but it is longer and thicker than the prokaryotic flagellum. The eukaryotic flagellum works by waving up and down like a whip. In higher animals, the sperm cell uses a flagellum to swim toward the female egg for fertilization.

Movement in eukaryotes is also

accomplished with cilia, short, hairlike proteins built by centrioles, which are

barrel-shaped structures located in the cytoplasm that assemble and break down

protein filaments. Typically, thousands of cilia extend through the plasma

membrane and cover the surface of the cell, giving it a dense, hairy appearance.

By beating its cilia as if they were oars, an organism such as the paramecium

propels itself through its watery environment. In cells that do not move, cilia

are used for other purposes. In the respiratory tract of humans, for example,

millions of ciliated cells prevent inhaled dust, smog, and microorganisms from

entering the lungs by sweeping them up on a current of mucus into the throat,

where they are swallowed. Eukaryotic flagella and cilia are formed from basal

bodies, small protein structures located just inside the plasma membrane. Basal

bodies also help to anchor flagella and cilia.

Still other eukaryotic cells, such as

amoebas and white blood cells, move by amoeboid motion, or crawling. They

extrude their cytoplasm to form temporary pseudopodia, or false feet, which

actually are placed in front of the cell, rather like extended arms. They then

drag the trailing end of their cytoplasm up to the pseudopodia. A cell using

amoeboid motion would lose a race to a euglena or paramecium. But while it is

slow, amoeboid motion is strong enough to move cells against a current, enabling

water-dwelling organisms to pursue and devour prey, for example, or white blood

cells roaming the blood stream to stalk and engulf a bacterium or virus.

| B | Nutrition |

All cells require nutrients for energy, and they display a variety of methods for ingesting them. Simple nutrients dissolved in pond water, for example, can be carried through the plasma membrane of pond-dwelling organisms via a series of molecular pumps. In humans, the cavity of the small intestine contains the nutrients from digested food, and cells that form the walls of the intestine use similar pumps to pull amino acids and other nutrients from the cavity into the bloodstream. Certain unicellular organisms, such as amoebas, are also capable of reaching out and grabbing food. They use a process known as endocytosis, in which the plasma membrane surrounds and engulfs the food particle, enclosing it in a sac, called a vesicle, that is within the amoeba’s interior.

| C | Energy |

Cells require energy for a variety of functions, including moving, building up and breaking down molecules, and transporting substances across the plasma membrane. Nutrients contains energy, but cells must convert the energy locked in nutrients to another form—specifically, the ATP molecule, the cell’s energy battery—before it is useful. In single-celled eukaryotic organisms, such as the paramecium, and in multicellular eukaryotic organisms, such as plants, animals, and fungi, mitochondria are responsible for this task. The interior of each mitochondrion consists of an inner membrane that is folded into a mazelike arrangement of separate compartments called cristae. Within the cristae, enzymes form an assembly line where the energy in glucose and other energy-rich nutrients is harnessed to build ATP; thousands of ATP molecules are constructed each second in a typical cell. In most eukaryotic cells, this process requires oxygen and is known as aerobic respiration.

Some prokaryotic organisms also carry out

aerobic respiration. They lack mitochondria, however, and carry out aerobic

respiration in the cytoplasm with the help of enzymes sequestered there. Many

prokaryote species live in environments where there is little or no oxygen,

environments such as mud, stagnant ponds, or within the intestines of animals.

Some of these organisms produce ATP without oxygen in a process known as

anaerobic respiration, where sulfur or other substances take the place of

oxygen. Still other prokaryotes, and yeast, a single-celled eukaryote, build ATP

without oxygen in a process known as fermentation.

Almost all organisms rely on the sugar

glucose to produce ATP. Glucose is made by the process of photosynthesis, in

which light energy is transformed to the chemical energy of glucose. Animals and

fungi cannot carry out photosynthesis and depend on plants and other

photosynthetic organisms for this task. In plants, as we have seen,

photosynthesis takes place in organelles called chloroplasts. Chloroplasts

contain numerous internal compartments called thylakoids where enzymes aid in

the energy conversion process. A single leaf cell contains 40 to 50

chloroplasts. With sufficient sunlight, one large tree is capable of producing

upwards of two tons of sugar in a single day. Photosynthesis in prokaryotic

organisms—typically aquatic bacteria—is carried out with enzymes clustered in

plasma membrane folds called chromatophores. Aquatic bacteria produce the food

consumed by tiny organisms living in ponds, rivers, lakes, and seas.

| D | Protein Synthesis |

Before a protein can be made, however,

the molecular directions to build it must be extracted from one or more genes.

In humans, for example, one gene holds the information for the protein insulin,

the hormone that cells need to import glucose from the bloodstream, while at

least two genes hold the information for collagen, the protein that imparts

strength to skin, tendons, and ligaments. The process of building proteins

begins when enzymes, in response to a signal from the cell, bind to the gene

that carries the code for the required protein, or part of the protein. The

enzymes transfer the code to a new molecule called messenger RNA, which carries

the code from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. This enables the original genetic

code to remain safe in the nucleus, with messenger RNA delivering small bits and

pieces of information from the DNA to the cytoplasm as needed. Depending on the

cell type, hundreds or even thousands of molecules of messenger RNA are produced

each minute.

Once in the cytoplasm, the messenger RNA

molecule links up with a ribosome. The ribosome moves along the messenger RNA

like a monorail car along a track, stimulating another form of RNA—transfer

RNA—to gather and link the necessary amino acids, pooled in the cytoplasm, to

form the specific protein, or section of protein. The protein is modified as

necessary by the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus before embarking on

its mission. Cells teem with activity as they forge the numerous, diverse

proteins that are indispensable for life.

1 comments:

Its Great, but you need to give a bit summary at the ending

Post a Comment