Click here if you are looking for a certified online tutor or home tutor

Reproductive System

| I | INTRODUCTION |

Reproductive

System, term applied to the group of plant or animal organs that are

necessary for or that are accessory to the reproductive processes (see

Reproduction). The basic units of sexual reproduction are the male and

female germ cells; this article deals with the organs within which the germ

cells of animals mature and are stored, the organs through which they are

transported in the process of producing a new individual, and accessory

glandular organs. For the reproductive organs of plants, see Plant

Propagation.

| II | ORIGIN OF THE REPRODUCTIVE CELLS |

When the embryo of any sexually reproducing

animal is undergoing cell division, certain cells, known as primordial germ

cells, which are produced by such division, remain in an undifferentiated state.

Cells other than primordial germ cells are known as vegetative cells or somatic

cells; these cells become differentiated into tissues and organs. In

invertebrates, the primordial germ cells congregate in the body cavity or in a

section of the circulatory system; in vertebrates, these cells are located in

organs that adjoin the excretory system. The tissues in which the germ cells

lodge become reproductive organs known as gonads. These organs are

embryologically derived from primitive kidneys located in the anterior, lateral

part of the body; in most mammals, they shift before birth to the posterior,

ventral region of the body. The primordial germ cells remain inactive in the

gonads until the animal reaches sexual maturity, when the undifferentiated cells

undergo a great number of normal cell divisions or mitoses. In the process of

developing into mature reproductive cells or gametes, the germ cells undergo a

special type of cell division, known as meiosis, which halves the number of

chromosomes they carry. At the time of sexual maturity, the somatic cells

composing the gonads of higher animals begin to secrete hormones that control

the appearance of the various secondary sexual characteristics (see

Sex).

| III | GONADS |

Organs that contain germ cells which later

develop into male gametes or spermatozoa are known as testes or male gonads.

Organs that contain germ cells which later develop into female gametes, eggs, or

ova are known as ovaries. In many invertebrate species individual animals bear

both testes and ovaries (see Hermaphroditism). In some invertebrates, and

in most vertebrates, individuals bear either testes or ovaries, but not both

sets of organs. In invertebrates, a single animal may have as many as 26 pairs

of gonads; in vertebrates, the usual number is 2. Cyclostomes and most birds are

unusual among vertebrates in possessing only a single gonad; owls, pigeons,

hawks, and parrots are unusual among birds in having two gonads. The size of

gonads increases at sexual maturity because of the great number of germ cells

produced at that time; many germ cells are also produced during breeding seasons

so that many animals have a seasonal increase in size of the gonads. During the

breeding season of fish, the ovaries increase in size until they constitute

about one-quarter to one-third of the total body weight.

The testes and ovaries of mature animals

differ greatly in structure. The testes are composed of delicate convoluted

tubules, known as seminiferous tubules, in which the primitive germ cells mature

into spermatozoa. The testes of mammals are generally oval bodies, enclosed by a

capsule of tough connective tissue. Projections from this tough capsule into the

testis divide the testis into several compartments, each of which is filled with

hundreds of seminiferous tubules. The mature spermatozoa are discharged through

a number of ducts, called the efferent ducts, which communicate with the

epididymis, a thick-walled, coiled duct in which the sperm are stored.

In all vertebrates below marsupials on the

zoological scale, and in elephants, sea cows, and whales, the testis remains

within the body cavity during the lifetime of the animals. In many mammals, such

as rodents, bats, and members of the camel family, the testis remains within the

body cavity during periods of quiescence, but moves into an external pocket of

skin and muscle, known as the scrotum, during the breeding season. In

marsupials, and in most higher mammals, including the human male, the testes are

always enclosed in an external scrotum. During fetal life, the testes move

through the muscles composing the posterior, ventral portion of the trunk and

carry with them the portion of the peritoneum and skin surrounding these

muscles. The channel in the muscles through which the testis moves is known as

the inguinal canal; it usually closes after birth, but sometimes remains open

and is then often the site of herniation (see Hernia). The portion of the

peritoneum that the testis carries with it forms a double wall of membrane

between the scrotum and testis and is known as the tunica vaginalis.

Occasionally, the testes in the human male do not descend into the scrotal sac;

this condition of nondescent, which is known as cryptorchidism, may result in

sterility if not corrected by surgery or the administration of hormones.

Retention of the testes within the body cavity subjects the germ cells to

temperatures that are too high for their normal development; the descent of the

testes into the scrotum in higher animals keeps the testes at optimum

temperatures.

Unlike germ cells in the testis, female germ

cells originate as single cells in the embryonic tissue that later develops into

an ovary. At maturity, after the production of ova from the female germ cells,

groups of ovary cells surrounding each ovum develop into “follicle cells” that

secrete nutriment for the contained egg. As the ovum is prepared for release

during the breeding season, the tissue surrounding the ovum hollows out and

becomes filled with fluid and at the same time moves to the surface of the

ovary; this mass of tissue, fluid, and ovum is known as a Graafian follicle. The

ovary of the adult is merely a mass of glandular and connective tissue

containing numerous Graafian follicles at various stages of maturity. When the

Graafian follicle is completely mature, it bursts through the surface of the

ovary, releasing the ovum, which is then ready for fertilization; the release of

the ovum from the ovary is known as ovulation. The space formerly occupied by

the Graafian follicle is filled by a blood clot known as the corpus

hemorrhagicum; in four or five days this clot is replaced by a mass of yellow

cells known as the corpus luteum, which secretes hormones playing an important

part in preparation of the uterus for the reception of a fertilized ovum. If the

ovum goes unfertilized, the corpus luteum is eventually replaced by scar tissue

known as the corpus albicans. The ovary is located in the body cavity, attached

to the peritoneum that lines this cavity.

The functioning of both male and female

gonads is under the hormonal influence of the pituitary gland.

|

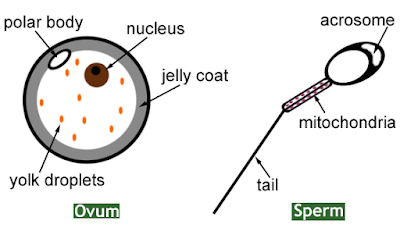

| Ovum and Sperm |

| IV | TRANSPORTATION OF THE REPRODUCTIVE CELLS |

Before being discharged from the body, the

reproductive cells travel from the gonads to an external body opening. In many

invertebrates, and in a few aquatic vertebrates, the reproductive cells are

discharged into water directly from the gonads through pores in the body wall.

In higher animals ducts carry the reproductive cells into the urinary or cloacal

excretory systems, or into independent reproductive passages.

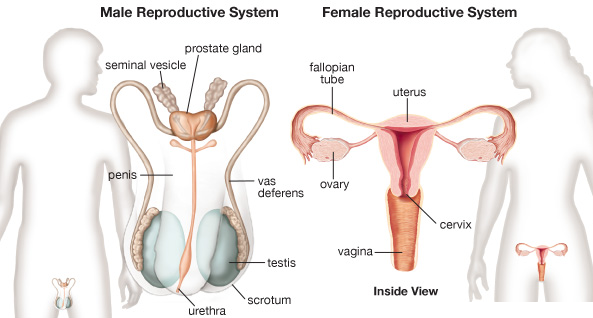

In male vertebrates, the ducts are directly

connected to the testes. The male ducts include the epididymis, which lies

attached to the testis, and which transports the male gametes to the vas

deferens. The vas deferens carries the spermatozoa to the ejaculatory duct, the

contractions of which cause the discharge of sperm into the posterior

urethra.

In most fishes, the ovary has a hollow

expansion through which the ova pass into the cloaca. In most other vertebrates,

however, no direct connection exists between the ovary and the oviducts that

carry the ova into the cloaca or into the independent external opening. In

mammals, when the Graafian follicle bursts, the egg falls toward the interior of

the abdominal cavity. The oviduct (known in higher mammals as the fallopian

tube) has an open, funnel-shaped end located near the ovary, and the mature egg

is drawn into the funnel by ciliary action. Occasionally, the egg misses the

open end of the oviduct and falls into the abdominal cavity; such eggs are

capable of being fertilized, resulting in ectopic pregnancies (see

Pregnancy and Childbirth). In animals lower than marsupials the oviducts

open directly into the cloaca; in marsupials and placental mammals, the

oviducts, two of which are normally present, fuse at their cloacal ends to form

a thick, muscular organ, the uterus or womb, in which the young develop, and a

thinner channel, the vagina, which opens exteriorly.

| sperm, ova |

| V | GENITALS |

In animals that lay their eggs and discharge

their sperm into water, the spermatozoa reach the eggs by chemical attraction;

the eggs of individuals of a species attract only the sperm of members of the

same species. When eggs and sperm are deposited at great distances from each

other, the number of eggs fertilized is small. Many amphibians and aquatic

vertebrates solve this problem by attaching themselves to their mates by means

of holdfast mechanisms, such as claspers; when the female of these animals

deposits the eggs, the male can immediately deposit sperm in the same

location.

In terrestrial animals, various adaptations

have been developed whereby internal fertilization of the eggs may be produced.

The male snake, which discharges the spermatozoa through a cloaca, has, for

example, anal hooks that are inserted into the cloaca of the female during the

breeding season. These hooks bind the male and the female together while the

spermatozoa are being discharged. External reproductive organs used by animals

to facilitate internal fertilization are known as genitals or genitalia.

The male genital of all mammals above the

monotremes is the penis, a protrusible, erectile organ that directs the

spermatozoa into the female cloaca or vagina. In turtles and crocodiles, which

are the most primitive animals possessing the organ, the penis is located on the

ventral wall of the cloaca and is grooved along its upper side. The spermatozoa

travel along the groove into the female cloaca. In marsupials and placental

mammals, the penis is a closed tube, composed of three bundles of tissue, bound

together by connective tissue and covered with loose skin. Two large bundles of

tissue, known as the corpora cavernosa, constitute the upper portion of the

penis; these bundles contain numerous compartments that are filled with blood

during sexual excitement, causing the penis to become stiff and erect. The flow

of blood into the corpora cavernosa is controlled by sacral spinal nerves. Below

and between the corpora cavernosa is the third bundle of tissue, which is known

as the corpus spongiosum; this bundle is perforated by the urethra and, in

several lower mammals, also contains a bone that serves to further stiffen the

male genital. At the terminal end of the penis is a sensitive cap known as the

glans; in marsupials the glans is forked. In many mammals, the male genital,

when not erect, is withdrawn into a sheath in the body. In primates, including

the human male, the penis is pendant, and the glans is covered with a layer of

retractile skin, known as the prepuce or foreskin, which corresponds to the

sheath of lower animals.

The chief female genital is known as the

vagina. This organ is present in all marsupials and placental mammals. In

marsupials, two vaginas and two uteri are present; in primates, including the

human female, only one vagina is present; and in mammals intermediate in

development between the marsupials and primates, various degrees of partially

united, double vaginas are present. The external end of the vagina is covered in

virgin primates by a membrane, known as the hymen. Anterior to the hymen is the

external opening of the urethra. The urethra and the opening of the vagina are

contained in an indented space which is known as the vestibule. In primates, two

membranous folds, known as the labia minora, are found on either side of the

vestibule. In primates, including the human female, two additional folds, the

labia majora, enclose the labia minora. The clitoris, at the front of the labia,

is homologous with the penis although greatly reduced in size (see Homology

below).

| VI | ACCESSORY GLANDS |

Among the glands accessory to the

reproductive process are those that provide a fluid medium in which the

spermatozoa may live, those that produce mucus which reduces friction during

copulation, those that emit alluring odors to members of the opposite sex, and

those that secrete nourishment for the ova, the embryos, and the newborn

young.

The seminal vesicles of the male have already

been mentioned as organs that secrete mucus. The most important male accessory

gland is the prostate gland, a compound gland about the size of a chestnut

located at the base of the urethra where the urethra leaves the bladder and

enters the penis. The prostate secretes a thin milky fluid with a characteristic

odor; this fluid constitutes the greater part of the semen that is deposited in

the female vagina and that contains the spermatozoa. The prostate gland is

present only in placental mammals, and among these mammals is absent in

edentates, martens, otters, and badgers. Cowper's glands are two small glands,

about the size of a pea, located on each side of the base of the penis. Their

secretion is thick and clear and is believed to protect the spermatozoa against

excess vaginal acidity. Cowper's glands are absent in bears, dogs, and aquatic

mammals.

The primary lubricating glands of the female

are the cervical glands, located in the uterus where the uterus communicates

with the vagina, and Bartholin's glands, located in the vestibule between the

hymen and the labia minora. Both sets of glands secrete mucus. Female placental

mammals also have uterine glands that prepare the uterus for the reception of

the fertilized egg.

The anal glands of many mammals secrete

special substances called pheromones, which signal reproductive readiness by

scent to members of the opposite sex. Pheromones may occur in other glandular

secretions as well.

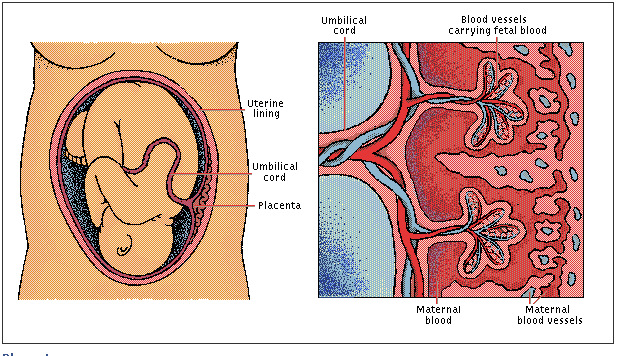

Among the different structures serving to

nourish the young, the placenta of placental mammals is unique (see

Fetus). The mammary glands of mammals are also included among accessory

reproductive glands (see Breast). Female egg-laying animals have albumen

glands, which coat the zygote with nutrient albumen before the egg is laid, and

nidamental glands, which surround the zygote and albumen with a leathery or

calcareous shell.

| VII | HOMOLOGY |

The sex of a young embryo is

indistinguishable, males and females passing through similar embryonic stages.

Embryo males and females develop almost a duplicate set of reproductive organs,

one set becoming vestigal shortly before birth, and the other set becoming

prominent. Most cases of so-called mammalian hermaphroditism are actually cases

of abnormal development in which external genitalia similar to those of both

sexes have been developed. For example, mammalian females have a small, erectile

organ, consisting of two corpora cavernosa, located in the upper portion of the

vestibule. This organ, called the clitoris, is homologous with the male penis;

except in lemurs and a few rodents it does not contain the urethra, which is

usually located beneath the clitoris. In species in which the male possesses a

penis bone, the clitoris of the female contains a small bone.